A Stir Is Born

The American Origins of an Italian Celebrity Chef

I must have been around ten when I started cooking, first with my mother and then with Betty Crocker—specifically, Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls. The recipes, tested by a panel of “twelve real boys and girls,” were heavy on desserts like Eskimo Igloo Cake and Paintbrush Cookies, but also savory classics like Pigs in Blankets, Mac & Cheese and Sloppy Joes.

I recently found a scanned copy of the original spiral-bound book in the Kindle store. Some of the recipes came back to me but I had no memory of the Candle Salad, which features a peeled banana, upright, poking from the center of a pineapple ring with a maraschino cherry on top. (The caption reads “It’s better than a real candle, because you can eat it.”) Me, I became a master of chocolate fudge—a skill that would serve me well decades later when, in 2020, I became the first and only American contestant on MasterChef Italia.

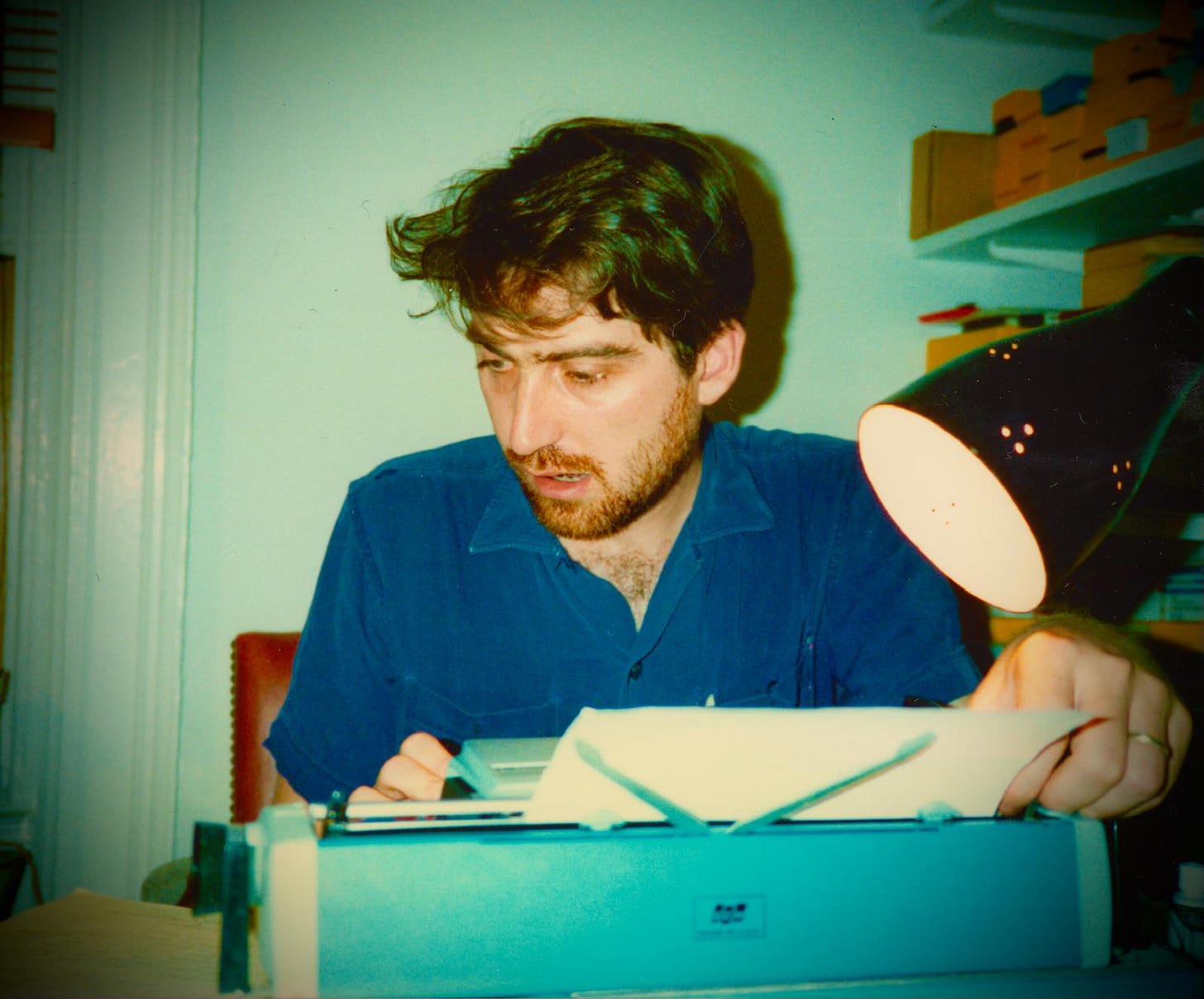

After high school I moved on from Betty Crocker, from chocolate and from cooking much at all—spending years in the culinary wilderness, so to speak, in an apartment in Providence with no stove. I worked as a bartender at a legendary (now gone) place downtown called Leo’s that was a town-and-gown melting pot of artsy RISD students; preppy Brown types; African-American jazz and funk musicians; and local Italian-American goombahs who worked in the costume jewelry factories above the bar and came in with hands blackened from the silver plating chemicals. This was way before “artisanal cocktails.” The students drank gin-and-tonics, the jazz musicians drank Scotch-and-milk, and the factory guys drank red-wine-and-Coke on the rocks which we started calling Coke-au-vin.

There I met Sarah, my future wife, where she worked as a cook. God was she beautiful. She would cook me dinner before my shift started—the menu was pretty classic American, burgers and chili, but also more daring fare like tabouli salad. Otherwise, those were the Takeout Years of my life. At home I basically ate out of cardboard boxes. (Much later in life, sneaking around China illegally on a motorcycle researching a novel, I learned the difference between “American” Chinese food and the real thing.)

But at age twenty-six I got accepted at Columbia to study art history, and Sarah was transferring to NYU. So we loaded up a U-Haul and moved to Brooklyn.

That was the Eighties, when Brooklyn was where you lived when you couldn’t afford Manhattan. There were no tapas bars on Smith Street, just grimy laundromats, car service storefronts run by Arabs, and red-sauce pasta joints that the New York Times never reviewed. If something fermented in your fridge you threw it away—it wasn’t “artisanal” anything.

We lived in the Italian neighborhood of Carroll Gardens, another mob zone which felt comfortingly familiar after years in Providence. It could be creepy—one time, walking home from the subway late at night, I saw a grown man slapping another man outside a bar. But there was a place that sold homemade fresh pasta, pancetta and all kinds of stuff from Italy like tubs of salted whole anchovies that, back then, barely existed in America.

So that’s when I started cooking again. I bought cookbooks and wore them out, breaking the bindings and staining the pages. Diana Kennedy taught me Mexican, Marcella Hazan opened my eyes to authentic Italian. From Huntley Dent (The Feast of Santa Fe) I unlocked the secrets of dried chiles and mastered what has become my show-stopping dinner-party dessert: coffee flan.

Oddly I never made my childhood specialty of chocolate fudge, but I scoured the city for rare Chinese and Middle Eastern ingredients (this was way before Amazon). I spent Saturdays traipsing through the Union Square farmer’s market, hauling bags full of Jersey tomatoes and garlic scapes on the subway back to Brooklyn. I grilled veal chops (illegaly) on a hibachi on our fire escape. I recall making tamales on Christmas Eve and osso buco on New Years Day.

On summer vacations in Maine where Sarah’s parents lived, I foraged chanterelle mushrooms on islands with her dad. I cooked lobsters a dozen different ways, then made a rich broth from their shells and put more lobsters and clams in that to make regal stews.

And then, in the summer of 1985, I took my first trip to Europe.

I flew Pan Am to Paris, got out of the metro at Châtelet and dragged my oversize duffel to a modest pension I had reserved near Hôtel de Ville. There I put a fresh press in a sport coat and went out, oblivious to jetlag, in search of my first meal in Europe. In those days the dollar was soaring and there were almost ten francs to the buck, which made Paris quite a bargain for a student on a budget. It didn’t take long to find a suitably affordable bistro with an outdoor table.

I can’t recall the wine, something ordinaire, but there was nothing ordinary about the escargots, tender and bathed in garlic butter which I sponged up with torn chunks of a crusty baguette. Then came the steak frites, which arrived rare and sliced and with a small ramekin of Bearnaise sauce. The large fries were crisp on the outside and soft as cake on the inside; when you tore one in half, wisps of steam trailed off and floated toward the Seine. After that was a salad of the most perfect leaf lettuce, cloaked in a mustard vinaigrette, followed by a small plate of oozing raw-milk Camembert with more of that baguette. I recall chestnut honey and walnuts. It didn’t hurt that the waitress, about my age with pale complexion and long dark hair tied up in a bun with tantalizingly uncooperative strands, was beautiful and kind.

The quotidian nature of this simple and classic Parisian meal made a deep impression. For the first time in my life, it dawned on me that there were places in the world where this was just normal food. Something you might eat every day, not a “gourmet” meal. This opened a whole new understanding of what it meant to eat well, and mindfully. And so that dinner, in an anonymous bistro near Les Halles on a June evening in 1985 with a waitress I shall never forget named only mademoiselle, marks the before and after of my life. I knew I would never be the same.

Sarah and I had been hired to work on an archeological dig in Provence, where she would join me later. I had rented a boxy Renault 11 and soon left Paris with a Michelin map that unfolded to the size of a banquet table, my route highlighted in yellow marker. The plan was to avoid the major toll highways and stick to the local and state roads, no matter how long it might take. Which was a week, careening through la France profonde. From Tours and the Loire Valley I steered south through Poitiers, Limoges, Oradour-sur-Glane, Aurillac. I slept in a tent in farmers’ fields. I bought cheese and wine and strawberries from local women in their barns, following the hand-painted signs for à vendre. At Rodez I cascaded down from the Massif Central to Montpellier and the wild Camargue region of the Rhône delta, finally reaching the walled medieval city of Aigues-Mortes on the Mediterranean, where some of the world’s finest sea salt is still harvested.

Nearby was our dig site, Psalmodi, a Gothic Benedictine monastery on top of a Romanesque church on top of a Carolingian church on top of an ancient Roman villa. It was a layer cake, but mostly underground or in ruins except for one side of the twelfth-century Gothic nave which was being used as the outside wall of a barn on a sunflower farm. (The flowers were grown for sunflower seed cooking oil, not table arrangements.)

Across a courtyard, the inside of another stone barn was our communal kitchen where we shared duties making dinner, often simple hearty stews but also codfish brandade, wild mushroom tarts with local cèpes, whatever inspired someone that day.

We slept in tents and had no hot water, just a cold hose shower behind the stables which was fed from a massive stone cistern outside the barn. One day they drained the cistern to clean it and found it was filled with eels. Everybody got ringworm. Everybody got blind drunk every night, emptying wine casks in the barn. Then we had to work the next day in the broiling hot sun, hung over. Before work, around 7:00 every morning, we staggered into the local village, Saint-Laurent-d’Aigouze, for a café au lait at the Café du Commerce, near the small bullfighting arena. The local vineyard workers—hard, rough men with stubby hands—were already quaffing their morning Pastis.

After the dig we had a two-week itinerary in Italy. To be honest, after spending most of the summer eating across France I was at first unimpressed by native Italian cuisine, despite having cooked versions of it regularly at home. Stripped of sauces and butter, lacking in richly caramelized and reduced broths, sparing of garlic, the food seemed…ascetic, almost disciplinary. That included panini, which in Italy are always just some slices of meat stuffed into a split ciabatta loaf with no condiments. Ever. And good luck asking for mustard which they won’t have. The same goes for most Italian wines, which are less tannic than astringent, because they are meant to be sipped with food, not guzzled at a gallery opening.

I chalk up a lot of this to my cultural ignorance at the time; Italians have a point when they complain that all those French sauces can mask less-then-optimal ingredients, whereas Italian dishes, simple and straightforward, have nowhere to hide. Thus the rhyming Italian saying: Troppe salse vivande false. Too many sauces, fake food. South of the Alps, more is not more. Italians never think that if a dish tastes good with parsley, it will taste even better with some basil, mint, oregano and thyme.

But my under-appreciation of Italian food was also due to being a naïve student tourist who didn’t yet speak Italian and was doubtless eating in a lot of touristy places—especially in Venice, for all its charms perhaps the world capital of rubber pizza.

That all changed in Rome.

If it can be hard to find a truly exceptional meal in the center of Rome, it was at least not difficult, in 1985 before the advent of mass tourism, to stumble upon a decent enough dinner. Blind as I was, I somehow tapped my way into countless unpretentious trattorias for plate after plate of pasta carbonara, cacio e pepe and amatriciana, to say nothing of braised oxtails, tripe stewed in tomatoes and (always on Thursday) handmade gnocchi in Gorgonzola sauce. I learned to love Roman style pizza with its thin, cracker-like crust.

Of course the experience of a meal is always bent by the prism of place—think how good a simple cold roast chicken tastes when enjoyed on a picnic alongside an even colder mountain stream. And so as I was falling in love with Roman food, I was also falling for Rome. Its ancient ruins, Renaissance palaces and Baroque churches need no description here—buy a guidebook. My Roman feast was served up in smaller portions: in its ochre travertine façades that glow in the afternoon sun as if lit by candles; the black lava cobblestone streets gleaming like patent leather pumps after a rain; the church bells exploding from every campanile, never in sync so they drop like a reggae drumbeat, not quite on the bar; and all of it set to the soundtrack of whining Vespas.

If that bistro meal in Paris marked my before and after, Rome determined the course of my future. Sarah and I were in love and would marry the next year. I had two more years of school, then we planned to have children. We loved New York, and this was all good. And yet…with no idea when or how it might ever happen, I knew that someday I would live in Rome.

Hungry awaiting the next

I was just settling in with an afternoon cup of tea on a very gray and very Maine Sunday in November expecting to read at least 10,000 words of and about how you got here and where you are going and then you just stop? Is that fair?